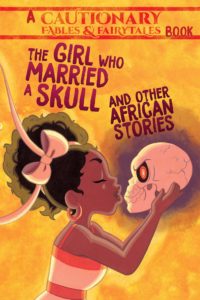

Happy Black History Month! I’ve been so backlogged with work that the only volume I knew I could do justice to with regard to the occasion this week is this graphic novel, a part of the Cautionary Fables & Fairytales Book series printed by Iron Circus. I got the entire collection several crowdfunds ago (and recently completed the set) but had never had the right time or occasion to dive in. Happily, I now have a reason to read at least one.

And what a delightful way to start, especially since this is, I believe, the first in the series? The fifteen black and white tales collected here were written and illustrated by seventeen different creators, with a terrific spread across all sorts of folk tales. From humor to horror, from creation myths to tales transposed to a far future, this variety pleases the folklore completist in me. While I’d heard of some of these stories in different incarnations — the title story is fairly widespread, at least to those with an interest in pan-African culture — I was absolutely struck by the whimsy imbued in each interpretation presented here. Perhaps it’s my current state of mind, too, that has me embracing these light-hearted and overall generous takes. The classic story of the girl who married a skull does not usually end as charmingly as it does in these pages, after all.

And what a delightful way to start, especially since this is, I believe, the first in the series? The fifteen black and white tales collected here were written and illustrated by seventeen different creators, with a terrific spread across all sorts of folk tales. From humor to horror, from creation myths to tales transposed to a far future, this variety pleases the folklore completist in me. While I’d heard of some of these stories in different incarnations — the title story is fairly widespread, at least to those with an interest in pan-African culture — I was absolutely struck by the whimsy imbued in each interpretation presented here. Perhaps it’s my current state of mind, too, that has me embracing these light-hearted and overall generous takes. The classic story of the girl who married a skull does not usually end as charmingly as it does in these pages, after all.

Of course, this is ostensibly a collection for children, which might explain the lack of grimness. Regardless of why, I’m here for it, as we read of daring protagonists who use their ingenuity for good (tho sometimes for bad — and believe me, that never ends well.) Aside from Nicole Chartrand’s The Disobedient Daughter Who Married A Skull, I especially loved Katie & Steven Shanahan’s Demane And Demazana; Carla Speed McNeil’s Snake And Frog Never Play Together; Kate Ashwin’s The Story Of The Thunder And The Lightning; D Shazzbaa Bennett’s Gratitude; Mary Cagle’s The Lion’s Whiskers; Ma’at Crook’s Queen Hyena’s Funeral, and Meredith McLaren’s Concerning The Hawk And The Owl. The stories are almost all outstanding, but these are the ones that really grabbed me, and married their words particularly well with their illustrations.