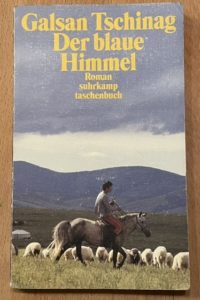

For some readers, Galsan Tschinag’s description of hard nomadic life in the Altai mountain region of Mongolia’s furthest western reaches in the 1950s will be enough. Der blaue Himmel — which could reasonably be translated as The Blue Sky or Blue Heaven — is a fictionalized memoir of a few years in a boy’s life, growing up in a family of shepherds in the Altai. As depicted in the book, it is a mostly self-contained, precarious, creaturely existence. Family members spend most of their time with the herds, and even the youngest have responsibilities as soon as they are able to fulfill them. By the time he is five or six, the narrator is looking after the small herd of sheep who cannot travel further afield — too young, too old, too lame, or temporarily incapacitated — to graze with the main flocks.

The family is not truly alone; in some seasons they keep their ger (Tschinag uses the word “yurt,” which seems still prevalent in German, while English was already trending toward the Mongolian term “ger” when I was there in 1999) near others from their extended family. The permanent settlement where the narrator will eventually follow his older siblings to school is less than a full day’s ride away. A medical emergency brings remedies from numerous sources, as word spreads among people willing to help. Nevertheless, Tschinag concentrates on a social world bounded by the narrator’s immediate family, most definitely including one dog (the family presumably has numerous dogs; this is so usual that a typical greeting as one approaches a ger is “Hold your dogs!”) that is very special to the narrator.