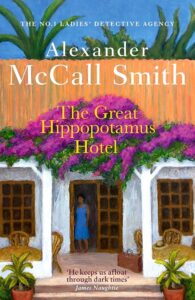

Three cases present themselves to the No. 1 Ladies’ Detective Agency in The Great Hippopotamus Hotel, the twenty-fifth book in Alexander McCall Smith’s long-running series. Well, if not necessarily cases then situations that Mma Ramotswe and Mma Makutsi feel obliged to untangle. Maybe not three, either, more accurately two and a half, given that one person, Mr XYZ turns out to play a crucial role in two of the situations. One of them, at least, is a proper case with a paying client. The other two come to them in ways that things do in Botswana, through the web of obligations and relationships that make up the community. Even though one of those is more an obligation that Mma Makutsi takes upon herself, and not for the noblest of reasons either, no matter what she tells herself.

In the first case — the one that is properly a case — the manager of the Great Hippopotamus Hotel speaks to Mma Ramotswe about troubles he is having with the hotel. Mma has seen signs for it on the outskirts of Gabarone and has been curious about the place, but has never had cause to visit. The manager, a man named Babusi, says the hotel has recently had a run of bad luck. Some guests have come down with food poisoning, and the timing there could not have been worse. It was a visit arranged for travel writers and other people who could, he hoped, share good news and improve the hotel’s reputation. Instead the exact opposite happened. Another time recently, a guest had found a scorpion in their shoe in the room. There were other unfortunate happenings, nothing that was inexplicable, but Babusi says it is looking like a pattern. He was also suspicious because the bad luck began shortly after the hotel’s long-time owner retired and passed ownership on to two nephews and a niece. Mma promises to investigate.

Separately, Mma Ramotswe’s husband Mr J.L.B. Matekoni is in a bit of a bind. A long-time customer whose brother owns a car rental company that provides Mr J.L.B. Matekoni’s garage with about a quarter of its income has asked him to buy a flashy sports car. That in itself is no problem; Mr J.L.B. Matekoni has automotive connections that reach beyond Botswana, and he will be able to find something suitable in South Africa. He even has experience managing the annoying bureaucracy of importing such a car. The problem is that his customer, Mr Mo Mo Malala, does not want his wife to know about the car. Mr J.L.B. Matekoni promised his help before he know about the condition of hiding it from Mr Malala’s wife. He cannot go back on his word, and if he did, his business could suffer. He explains the situation to Mma Ramotswe, but she does not see any immediate way out either.

Continue reading

translated from the original Czech by Martha Kuhlman.

translated from the original Czech by Martha Kuhlman.