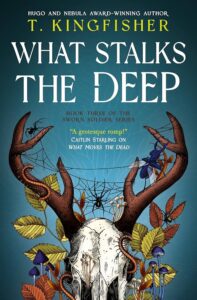

T. Kingfisher’s third Sworn Soldier novella — following What Moves the Dead and What Feasts at Night — takes Alex Easton and their* batsman Angus to America at the urgent behest of their friend James Denton, a doctor last seen by readers not far from where the House of Usher had fallen. He had returned home, still shaken, only to encounter … something that spooked him enough to send a telegram imploring Easton to come “with all haste.” (p. 10)

Upon their arrival in Boston, Angus and Easton are met by Denton’s assistant Kent. He takes them from the harbor to their hotel, where Denton and his friend John Ingold are waiting in the dining room. Denton, it transpires, has inherited an abandoned coal mine in West Virginia, among many other things. His cousin Oscar recently disappeared while investigating the mine, and Denton wants Easton’s help finding out what happened.

Denton coughed. “At any rate, it’s your experience with … unusual … circumstances that I need.”

I raised an eyebrow. Angus raised both of his. “You mean like what we saw at Usher’s lake,” I said flatly. “Because I’ll tell you, that was the first time I’ve dealt with anything like that.” …

“The first time for me, too,” said Denton. He looked suddenly weary and much older than I remembered. “But you did deal with it, and you know there are terrible things in the earth. If you encounter another one, you won’t waste time insisting that there must be a different explanation or that I’m lying to you or that none of this can possibly be happening.”

Terrible things in the earth. Yes. Denton and I had seen a terrible thing in the earth and ended it … (pp. 16–17)

Oscar, Denton relates, had “always liked digging, whether it was papers or actual dirt.” (p. 19) He was the one who discovered the deed to the mine, which had been abandoned for decades. He was experienced with caves, and wanted to try to figure out why the mine had been abandoned. At first, Oscar sent regular letters. Then he sent one about observing unusual phenomena in the mine. What Stalks the Deep is a creepy adventure story, but it is also very much a T. Kingfisher book, as the next paragraph shows:

Ah, I thought. The sort of person who talks about “observing phenomena.” I actually quite like people like that, because if you can get them talking about their particular specialty, they will tell you the most fascinating anecdotes about bottles or ball lightning or things they have extracted from some unfortunate soul’s rectum. They can be immense fun at otherwise stuffy parties. (p. 21)

Oscar had been exploring the mine and working with a local assistant named Roger. Oscar’s letters describe odd things that they had been seeing and hearing in the mine, and one ends with an inexplicable wonder. It was also the last letter that Denton received.

Denton, it was a marvel. A chamber a hundred feet across, floored with some gemstone that I have never seen before. It was perfectly smooth, almost like glass, and shone like mother-of-pearl, and it glowed in the darkness with a light strong enough to read by.

I have never seen anything like it. It was beautiful and impossible and it filled me with the awe and dread that only the inexplicable can invoke. I do not know how such a thing came to be.

The gemstone was too hard to break off, and Roger certainly tried his best. …

You must come and see it, for I can hardly believe my own eyes and would be grateful for someone else’s. …

Please come at once. This is an extraordinary find, and one which deserves to be brought before the eyes of men of learning. (pp. 27–28)

Denton departed immediately, but Oscar was nowhere to be found. He stayed a couple of days, failing to locate his cousin. Upon his return to Boston, he found a telegram waiting for him, one that ended “HOLLOW ELK MINE IS OF NO INTEREST STOP.” (p. 29) Ingold is a man of learning — a chemist who used to work for Du Pont — as well as Denton’s upstairs neighbor and a close friend. As the discussion continues, it’s clear that he and Denton have been arguing about Oscar’s fate nearly the whole time it took Easton and Angus to travel to Boston. It’s equally clear that the only way to know is to travel to Hollow Elk Mine to find out what they can learn at the scene of Oscar’s disappearance.

Along the way, Ingold mentions some things they might have to worry about in the mine, apart from whatever is causing the red lights that Oscar observed and whatever is the source of the marvelous chamber: “The real problem is likely firedamp. Also black damp, white damp, and stinkdamp.”

“That seems like a great many damps,” [I said].

“Oh yes. Firedamp is what they call methane. It seeps out of the coal and rises. It’s extremely flammable and highly explosive.” Ingold grinned. “Best of all, it’s completely odorless, so we’ll have no idea it’s there until the shaft explodes.”

I edged away from him on the seat. (p. 39)

Ingold explains more of the damps, which either explode or smother you, or both.

“And what was that last one?”

“Stinkdamp. Hydrogen sulfide, smelly like rotten egs. That one, at least, is pretty uncommon.”

“Does it explode?” Angus asked, sounding resigned.

“Of course it does,” said Ingold, as if surprised that he even had to ask. (p. 40)

Beneath the banter, the mystery remains unsettling. What happened to Oscar? When they get to the area, the local people clearly know a bit more, and they say the mine always had a bad reputation, but they are reluctant to give any details. Everyone is further unsettled by evidence of what looks to have been bear attacks on animals and livestock, but with details that do not suggest normal bear behavior. The five from Boston do find Roger, but he’s been so consistently drunk since Oscar’s disappearance that talking to him brings them no closer to any conclusions. His enormous and aggressive dog limits conversation, too.

There’s nothing for it but to explore the mine themselves, and they soon see some of the same things that so puzzled Oscar. Kingfisher keeps the story tense all the way through, emphasizing the cramped quarters in the mine, and all of the things that can go wrong in an active and well-run mine. Which Hollow Elk most emphatically is not.

Ingold thinks that what Denton experienced with the Ushers is driving him to recklessness. Denton had trouble regaining his equilibrium after returning home to Boston, and the thought that a repeat experience could be happening so close has taken that sense of safety away. Plus, he and Oscar were unusually close cousins, and he cannot stop without knowing. All of them delve deeper and deeper, as developments get stranger and stranger. Along with the damps.

The answers when they come — for this is not a book that denies readers an explanation — are unsettling and wondrous. Easton has a couple of Murderbot moments along the way — “And now we were talking about feelings. I would almost rather he had poured the burning oil on me.” (p. 179) — and there are surprises right up until the very end. What Stalks the Deep takes its people to new shores, to literal and figurative depths, and keeps what made the first two enjoyable novellas while adding to their characters and the wider world. Even better, Kingfisher closes with the promise of more stories of Easton and company.

+++

* Easton’s native Gallacian language has a surprising number of pronouns, including those that apply only to soldiers, and within the story Kingfisher applies those to Easton. Outside of the story, they/their is less confusing, and Kingfisher also follows this practice on the book’s cover copy.