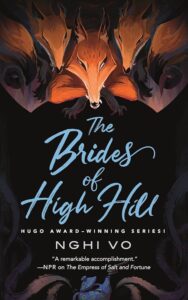

In the two most recent Singing Hills books — The Brides of High Hill and A Mouthful of Dust — Nghi Vo takes her protagonist, the historian Cleric Chih, to much darker places than in the three previous books of this series that I have read. (Those are, in order, The Empress of Salt and Fortune, When the Tiger Came Down the Mountain, and the fourth, Mammoths at the Gate. I’ve not yet read the third, Into the Riverlands, but it’s on order so I hope to have read and written about it by the time the seventh, A Long and Speaking Silence is published in May 2026.) As a refresher, all of the novellas are set in the Anh Empire, which draws on the history, fantasy and folklore of East Asia. Singing Hills is an ancient cloister, devoted to preserving history. To that end, they dispatch their clerics throughout the known world to collect stories, not just of the famous and the powerful but also of the everyday. Their efforts are aided by neixin, memory spirits that take the form of talking hoopoe birds. Clerics from Singing Hills wear distinctive indigo robes, shave their heads and use the pronoun “they.” Vo’s novellas all follow Cleric Chih on their journeys, accompanied by their hoopoe, Almost Brilliant.

The Brides of High Hill begins with Chih awakening from a dream. They are traveling on an ox cart that belongs to the Pham family, and Almost Brilliant is not present. Vo starts the story in media res, with no details of how they came to be traveling together, or whether Chih has had a particular set by the abbey. Master and Madame Pham are taking their daughter Nhung to be married to the Lord Guo, master of Doi Cao. The bride-to-be is young and nervous. Chih is quite taken by Nhung; maybe the feeling is reciprocated?

“I like stories,” said Nhung, and she took Chih’s hand in hers, smiling shyly.

“That’s good, I have a lot,” Chih said, momentarily enchanted by Nhung’s smile. She smiled close-lipped with one side higher than the other, and it was the prettiest thing Chih had ever seen.

The ox-cart swayed, and Nhung momentarily fell against Chih’s side. Her silk robes puffed with the scent of rosewood, and underneath that, Chih, blushing, could smell her skin and her sweat… (p. 3)

Nhung has been trained in how to run a household, and she hopes she will be a good wife. Chih says they hope her new husband will be worthy. The Phams are proud, and they have guards and retainers in more ox-carts behind them, but the family’s fortunes are not what they once were, as Madame Pham is quick to point out.

“Worthy, unworthy!” cried Madame Pham. “Who gets to speak of worthiness when your father’S ship foundered off the coast of the Verdant Islands, when my rotten brother took your grandparents’ estate and gambled it away. Worthy is wealthy, cleric, wealthy enough to keep my precious daughter comfortable all her days.” (p. 5)

Soon thereafter, the train of wagons arrives at Doi Cao, a beautiful if slightly eccentric estate inside of thick walls that were built to withstand assault by war mammoths. Lord Guo, a large and imposing man of about sixty years, greets the new arrivals. As the formalities go on at ever greater length, Chih wanders off, is rebuffed in an attempt to help with the unpacking, and is startled by someone who says “Poor girl.”

“Hello,” Chih said cautiously. “Why do you say that?”

The young man turned to them. Full on, it was easy to see that he was some relation to Lord Guo … Chih expected him to say something about the difference in ages, which was great, or the elder Phams’ increasingly obsequious bows.

“Tell her to ask him to how many wives he’s had.”

The young man’s face twitched, a pained grimace that had some kind of horrible humor in it.

“They’re not in Shu.” (p. 12)

Doi Cao clearly holds sinister secrets. Can the Phams really be that indifferent to what’s waiting for their daughter? Can Nhung be that wide-eyed and innocent, or that tied to duty? Can Chih do anything about the situation? Where has Almost Brilliant gone?

As Chih said on the ride to Doi Cao, she has a lot of stories. But she’s not the only one. The Phams, Lord Guo, the peculiar young man, and numerous people who work on the estate all have their stories. Some of them are willing to talk, some of them are not, and some of them cannot. The clerics of Singing Hills are committed to telling true stories, but is anyone else? As Nhung’s wedding approaches, the signs only become more sinister, and Vo shows that she is willing to follow them all the way to the end. The violence that was consigned to the past in The Empress of Salt and Fortune or kept at bay by cleverness in When the Tiger Came Down the Mountain turns up in full fury in The Brides of High Hill, though not in a way that I expected.

Violence lurks in the background of A Mouthful of Dust as well. Cleric Chih has accepted an assignment to learn more about the town of Baolin, where “a famine demon had scorched the land just eighteen years before.” (p. 3) Almost Brilliant has returned as their companion, but in an ominous omen, not far from Baolin the two of them unearth teeth, shards of human bone, and scraps of green cloth. They say a prayer over the remains, then wrap them up with the intent of finding a graveyard or a temple later on.

According to Chih’s notes, the town of Baolin was only famous for three things. The first was the black soil … so strong and rich that it could grow a field of leopard melons from one full moon to the next.

Baolin also gave its name to Baolin pork. Baolin pork was slow roasted overninght in a thin dressing brould from, among other things, macerated melon, bulbs of mountain garlic, and oil pressed from a local bony fish. The dish was sticky and sweet with plenty of imitators all over the world, but a young cook had become the adviser to the king of Zhou with just that single recipe.

Finally, Baolin was known for its famine.

Eighteen years ago, a famine demon came to next in the valley. Its white plucked skin stretched over its sharp bones like the canvas of a medicine tent, and when it arrived, it drove away the water and then brought too much, sickening everything it touched with mold and rot. A man who had seen it clearly on a cold and biting night said that it walked sometimes on two limbs and sometimes on four, its clawed wings coming down to help it scutter across the ground. When it looked in his direction, he fell down into a violent fit of pure terror. (pp. 4–5)

Eighteen years have passed, though, and as Chih approaches, Baolin looks calm and prosperous. Vo then reveals a little bit about Chih’s background, about which she has been very sparing throughout the series.

… Chih wondered if the village of their birth looked like this … with no trace of the deprivation that came before. When they were two years old, the Boneyard River had risen out of its banks in a rage. The people took to the highlands, where they ate insects, bark, and grass, and, when even those were exhausted, each other. (p. 5)

Nor does Vo shy away from the terrible consequences of famine, and their predictable course.

There was no doubt that the people of Baolin had eaten one another. It was what people did in the face of starvation. They had done it in the highlands the year Chih’s birth family fled, they did it a year ago during the siege of the walled city of Shengzhi, and they did it after the Battle of the Eight Mammoths more than a hundred years ago. The archives at the Singing Hills abbey … were full of such incidents. Where there was hunger, there was desperation, and eventually, the belly cried louder than the children, or the elderly, or the dead. (pp. 5–6)

In a way, it’s comforting that the causes of famine in Chih’s world are literal demons. In the real world, while natural disasters can lead to localized or regional crop failures, it is the decisions of political leaders that lead to famine. During the Irish Potato Famine, some regions continued to export food, while British policy limited aid. China’s great famine of 1959–61 stemmed from a number of policies in the Great Leap Forward. The Ethiopian famine of the 1980s took agricultural disruption of the 1970s and added a multi-front civil war. Famine in the 1930s in Soviet Ukraine was deliberately engineered to break resistance of the peasantry to collectivization, and forced requisitions in the region were used to supply food exports. Compared with the horrors that humans with power inflict on other people, a demon that can be propitiated or distracted is almost welcome.

It isn’t really welcome, of course, because the three-year famine that the demon brought to Baolin brought horrors that people are reluctant to reveal a generation later. Upon arrival in Baolin, Chih acquires a white kitten, makes friends with a small girl, and, ironically enough, sits down to a delicious meal.

The broth when it came was well-strained, almost clear and with only chicken and salt to flavor it; the greens had a peppery flavor and were served raw, fresh enough that Chih found a small worm fallen on the edge of their bowl. They passed the worm to Almost Brilliant, who took it graciously from their fingertips. The kitten peered at the plate curiously, but when nothing good was forthcoming, she curled up on the bench by Chih’s hip and fell immediately into a nap.

Chih dutifully made some notes about the food, which was good, but hardly exceptional. As they wrote, however, they became aware of a delicious smell, salty and smoky but above all sweet, and a few minutes after that, the young man appeared with a plate of pork medallions spread in a deliberate fan with a fat nest of buckwheat noodles coiled to one side.

“Eat up,” he urged, setting it down in front of them. “It doesn’t get better than this.”

It had been a long time on dried fish and packets of rice wrapped in waxy leaves, and for a while, Chih just concentrated on eating the famous meal that had been set in front of them. The pork was delicately veined with fat, falling-apart tender and so sweet it had to be eaten a bite apiece with a mouthful of chewy noodles to cut through the richness. A dash of chili paste stirred into the noodles added just the right kind of vinegary heat, and Chih forced themself to slow down before they inhaled the whole thing. (pp. 10–11)

After the meal, the young man, whose name is Li and whose extended family are the original purveyors of Baolin pork, tells Chih the story of how his mother encountered the famine demon, how she survived, and what that has meant for the family in the years since. Mere moments after Chih has recorded the story, guards in the service of Magistrate Liu enter the restaurant in a clatter and command that Cleric Chih stay in his house during their time in Baolin. That, it transpires, means that all interviews will take place in the magistrate’s house as well, limiting what people are willing to say.

But people love to talk, as journalists and historians know, and no narrative stays controlled. Chih takes interviews as they come, and each adds a bit more to the story that will eventually find a home in the archives of Singing Hills. For example, Pi, the town’s head mason, tells Chih the tale that gives the novella its name.

… he did tell Chih about the thin cookies they made with clay when things got very bad. The cookies were baked in the small oven at the masons’ meeting house, thin as the blade of a trowel, pale and round as the moon.

“They tasted a little salty, and if you held the dust in your mouth for a little while, you imagined that it grew sweet,” Pi said. “We made them by the dozens and sold them for almost nothing. We all knew they were just dust.”

Chih licked their lips, imagining the snap of the cookie between their teeth, the puff of dust settled over their tongue.

“But people bought them anyway.”

“Of course,” Pi said, looking up in surprise. “There was barely anything else.” (p. 39)

Eventually Chih learns more about the magistrate, who had survived an earlier famine in Zhan. She even learns what all of that has to do with a white kitten and the bones they found outside of Baolin. Vo builds the menace around Chih’s mission slowly but relentlessly. As in The Brides of High Hill, she follows when the narrative takes her characters to a very dark place, where desperation reveals what some people are willing to do for another chance to live. I admire her willingness to take a series that had previously been long on charm into stories that show some terrible things. They’re not entirely bleak, and the terrors are mostly in the past, but they are by no means sugar-coated.

About two-thirds of the way through this novella, Vo gives the closest thing yet to a credo for Cleric Chih:

As a man who had survived [famine-stricken] Zhan, Magistrate Liu was extraordinary. Everyone who had survived Zhan was extraordinary. So was everyone who hadn’t survived it. There were small stories and strange stories and stories that were just outright lies, but the Singing Hills taught that there was no such thing as an insignificant story. (p. 64)