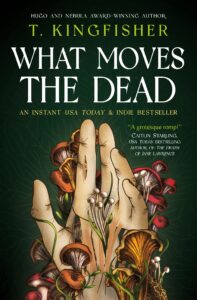

When T. Kingfisher, whose real name is Ursula Vernon, was re-reading “The Fall of the House of Usher” two things struck her. The first, as she writes in her author’s note at the end of the book “was that Poe is really into fungi. He devotes more words to the fungal emanations than he does to Madeline.” (p. 171) The second was that, for all the story’s staying power and cultural footprint, it’s short. The length left her wanting explanations. “I wanted to know about Madeline’s illness and why Roderick didn’t just move … it was blindingly obvious to me that Madeline’s illness must have something to do with all that fungus everywhere.” (pp. 171–72) Poe’s first-person narrator remains unnamed, but Kingfisher quickly came up with a name, and a backstory, and quite a lot of cultural background, including locating the Ushers’ house in Ruravia and bits of the narrator’s native Gallacian language.

The setup echoes “Usher”: the narrator travels to the isolated country manor house of an old friend, answering a summons that alludes to a mysterious illness, only to find the patient in dire straits and the surrounding circumstances far stranger and more disturbing than could have been expected from the letter. Alex Easton and Roderick Usher had been soldiers together in the recent war; before that, they were acquainted in their younger years with Roderick’s sister Madeline in the same circle. In expanding the story to novella length, Kingfisher adds characters and background. For example, the Gallacian language has an improbable number of sets of personal pronouns, including ka/kan, which is used exclusively for soldiers.

The Gallacian army fared poorly in many of its wars, leading to a shortage of men available for service. Some years before What Moves the Dead, a woman had presented herself to a recruiter and noted that nothing in the statutes said that she could not serve, as all references to soldiers referred to ka or kan, not once to he or him, nor she or her. She became the first sworn soldier of Gallacia and was ka/kan thereafter. Easton is similarly sworn.

Shortly before reaching the Ushers’ abode, Easton encounters a traveling Englishwoman, Eugenia Potter, an artist and mycologist. Apparently the area is extraordinarily suitable for fungi and mushrooms of all sorts, including at least one that Potter suspects is unknown to science. At the Ushers’ house, Easton also finds James Denton, a doctor, though most of his experience was battlefield surgery. He’s an American, of all things. In due course, Easton’s batsman, Angus, catches up.

While Kingfisher takes on the structure of Poe’s tale, its execution is unmistakably her style.

What was it about the house and the tarn that was so depressing? Battlefields are grim, of course, but no one questions why. This was just another gloomy lake, with a gloomy house and some gloomy plants. It shouldn’t have affected my spirits so strongly.

Granted, the plants all looked dead or dying. Granted, the windows of the house stared down like eye sockets in a row of skulls, yes, but so what? Actual rows of skulls wouldn’t affect me so strongly. I knew a collector in Paris … well, never mind the details. He was the gentlest of souls, though he did collect rather odd things. But he used to put festive hats on his skulls depending on the season, and they all looked rather jolly. (p. 10)

Madeline is indeed terribly ill; Roderick thinks she is dying. Kingfisher likes fungi too, but unlike Poe she gives Madeline plenty of words so that readers see the lively sister who inspires Roderick’s devotion. Kingfisher does get to exercise her mycological interests as well, particularly in an exchange between Lt. Easton and Miss Potter:

She tapped her parasol against the pebbles of the beach. “That said, mushrooms are not the only fungus. There are many, many types in the world We walk constantly in a cloud of their spores, breathing them in. They inhabit the air, the water, the earth, even our very bodies.”

I felt suddenly queasy. She must have read my expression, because a rare smile spread across her face. “Don’t be squeamish, Lieutenant. Beer and wine require yeast, as does bread.” (pp. 49–50)

The tale continues, with humor as dark as the lake before the Ushers’ house.

It was a sign of how disordered my nerves had become that I did not derive nearly enough enjoyment from hearing Miss Potter pronounce the word “nematode” with an accent so British that it very nearly had its own stiff upper lip. I could only imagine packs of mushrooms leaping across the moors in pursuit of prey. It should have been funny. I told myself firmly that it was funny. (p. 118)

And when things get definitively worse:

The English, in my experience, make an enormous deal about the most minor inconveniences, but if you confront them with something world-shattering, they do not blink. Miss Potter did blink, but only once, and then she looked down at he magnifying glass and said, “I see.” (p. 124)

Once What Moves the Dead gets rolling — and true to its nineteenth-century source, it has a slowish start — it is as wonderfully creepy and unsettling as I could wish for. Expanding Poe’s tale to novella length gives it more room to breathe, for the characters to come into their own, and for new personalities to try to prevent, and then survive the fall of the House of Usher.

1 ping

[…] Easton, sworn soldier of Gallacia and first-person narrator of What Feasts as Night as well as What Moves the Dead, delivers that meditation about halfway through the novella, when they are well past the unpleasant […]