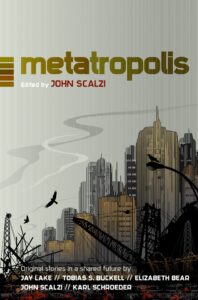

METAtropolis brings together five stories set in a nearish-future United States that’s mostly come undone amid climate catastrophes and other less-specified degradations. The anthology began as an audio-only collection. John Scalzi put it together, and worked with the other authors — Jay Lake, Tobias S. Buckell, Elizabeth Bear, and Karl Schroeder — to create a shared setting for their tales. Scalzi notes in his introduction that Medea: Harlan’s World, edited by Harlan Ellison, was something of a model, although I suspect that the worldbuilding for METAtropolis was more collaborative.

The audio anthology grew in two different directions. Three more all-audio collections followed in 2010, 2013 and 2014, with editorship passing to Jay Lake. The second, METAtropolis: Cascadia, won an Audie in 2012 for Original Work. Meanwhile, the first collection went into print, first as a limited edition from Subterranean Press in 2009, then a hardback from Tor in 2010, and then the trade paperback edition that I own was published in 2013. Five years of public and publisher interest in an anthology is unusually good. In the case of METAtropolis, I think it comes from three factors. First, and probably least important, there are people like me who are avid readers but haven’t really made room in their lives for audiobooks. I’m happy that I can enjoy the fiction on pages, even belatedly. (I haven’t yet picked up Scalzi’s series of audio-first novellas, but I am glad they are available in other formats.) Second, the overall idea is a neat one, and shared-world anthologies or series in fantasy and science fiction have a fun history. While METAtropolis did not grow into a large-scale project like Wild Cards or 1632, three sequels is perfectly respectable. Third, and probably most important, the authors were all well-known within the field, and each brought some of their fans, and their continued success led to more and more people discovering the anthology. By the time I picked up an autographed copy in a Chicago airport in 2015, the collection had a solid history.

Then my paperback spent ten years in TBR-land (where it was, alas, by no means the longest-term resident), and late teens is an awkward age for science fiction. The ideas that were new and bright and shiny at the time of publication may have aged poorly. Some of the projections may have come to pass, while others may have been shown to be absurd. The conversation among works of science fiction may have simply moved on, and in different directions; the concerns of one decade are by no means guaranteed to continue into the next. In short, the period between new and classic can be a rough one for works of art. The good news for readers is that METAtropolis fares reasonably well in that regard. It was not so perfectly fashionable in 2008 that it’s indelibly associated with the moment. The authors, as good artists, tackle human questions that recur, regardless of the window dressing of a particular story.

The central conceit of METAtropolis is that the countries of North America have failed to meet the challenges of the twenty-first century, and people have to find new ways to live. The United States has not vanished or collapsed so much as it has receded. The people of the book’s five stories are living in the cracks, the shadows, in spaces that the state can inhibit but not inhabit, trying to find local solutions to global problems that they cannot master. Jay Lake’s “In the Forests of the Night” features a hidden polity that’s something like a city, partly hidden, partly literally underground. He shows how this settlement defends itself, and what happens when it receives a transformative visitor for whom those defenses are not so much an obstacle as simply irrelevant. “The Red Sky is in Our Blood” by Elizabeth Bear and “Stochasti-city” by Tobias S. Buckell both consider, from different perspectives, ideas about distributed organization, how collective actions can happen without collectivities, and what kinds of actions that might work for. I don’t think the political and economic ideas in the book stand up to serious scrutiny — states are a lot more tenacious than the scenarios seen her allow for, and the industrial base required for the technologies the characters use is much larger than the scale of the stories allow for — but they are at the very least fun to consider. If pressed, I would say that the Scalzi story, “Utere Nihil Non Extra Quiritationem Suis” (loosely, “Use Everything But the Oink”) holds up best because it settles for technology that is loosely plausible and concentrates on what the character do with and to each other. Plus it’s funny. The last story in the collection, “To Hie From Far Cilenia” by Karl Schroeder, leans into the meta plays with the notion of virtual polities that run in parallel to the “real” world, and that there may be further worlds within those virtual worlds. It reminded me of Gnomon by Nick Harkaway and Dave Hutchinson‘s Fractured Europe series (both published much later), but more compact. METAtropolis brings together interesting ideas and well-constructed stories. For science fiction at an awkward age, that’s pretty good.