For the first three-quarters or so of this book, I was absolutely enthralled. Qian Julie Wang tells the story of her relatively prosperous, if politically oppressed life in Northern China before her Ba Ba emigrates to America, followed by herself and her Ma Ma five years later. They overstay their visas, becoming undocumented while Ba Ba and Ma Ma work a series of awful jobs to scrape together a life in Brooklyn, constantly dodging anyone who might seem to want to deport them. Qian struggles in school even after teaching herself how to read English, less due to her innate abilities than to the less than nurturing attitudes of certain teachers.

As the years pass, the corrosive effect of living in the shadows takes its toll on the small family, coming to a head when Ma Ma is hospitalized. Even after her recovery, Ma Ma is further disillusioned by her inability to become documented and thus get a job worthy of the qualifications she’s worked so hard to achieve both pre- and post-immigration. So Ma Ma takes a drastic step, and Qian is finally set on a certain path to freedom from the fear of losing everything she loves because of arbitrary employment and status regulations.

As the years pass, the corrosive effect of living in the shadows takes its toll on the small family, coming to a head when Ma Ma is hospitalized. Even after her recovery, Ma Ma is further disillusioned by her inability to become documented and thus get a job worthy of the qualifications she’s worked so hard to achieve both pre- and post-immigration. So Ma Ma takes a drastic step, and Qian is finally set on a certain path to freedom from the fear of losing everything she loves because of arbitrary employment and status regulations.

So, as an open borders absolutist, books that expose the completely ridiculous ways in which people contort themselves to justify denying human rights to migrants are totally my jam. Towards this end, Beautiful Country knocks it out of the park. It’s a stain on the moral character of any peoples who allow migrants to work for pennies under inhumane conditions, as the entire Wang family is forced to do. Some of our citizens even have the nerve to decry a shortage of skilled labor while refusing to extend protections to the qualified, further making up arbitrary reasons to harm the vulnerable while still profiting from their exploitation. Jackasses like these don’t see immigrants as people, only tools.

Fortunately, we have books like Ms Wang’s that highlight the humanity of the undocumented by depicting with complete frankness all the trauma that a life of poverty, enforced only by a lack of documentation (which, let’s be honest, is fundamentally due to racism,) inflicts upon her and her parents. She has the self-awareness to show how kindness and understanding require effort that the impoverished and hungry often simply can’t afford, freely admitting to having been kind of a shit herself, while still calling out the people who don’t have this excuse, whose experiences are so limited to their lives of relative privilege that they don’t even ask why a child would behave in seemingly self-sabotaging ways, instead assuming it’s because she’s lazy or indifferent. She catalogs both the people who were kind to her as well as all the ways people were gratuitously unkind, including in this last list her parents and the bizarre pronouncements they would lay on her. It’s fascinating and heartbreaking to follow along with a maturing Qian as she sees her father become exactly the opposite of who he’d wanted to be, why he’d left China in the first place.

And yet, the book didn’t land with me as emotionally as it might have. Ms Wang and I don’t share the same sense of humor, which probably doesn’t help. I appreciate hiding in the bathroom as much as if not more so than anyone else, but felt it kind of weird that so much time was spent on her bowels without finding a proper, or even any, diagnosis for her childhood ailments. More crucially, the end run Ma Ma makes to solve their problems feels under-explored and, frankly, dissonant with the rest of the memoir. I definitely felt for Canada in the way they essentially rescued an abused family only to have the youngest turn around and run right back to her abuser as soon as she was able. I understand Ms Wang’s motivations on a visceral level but I really wish she had explored the topic in greater depth. It’s one thing to say that NYC was so important to her formatively, and that her father would rather eat America’s shit than China’s fruits, but a thoughtful examination of why this is would have helped anchor the ending with greater meaning — after all, just because I feel a certain way doesn’t mean that’s how or why she did, and I’m basically reading this book because I want to hear her thoughts and opinions. As it is, the chapters about Ms Wang as an adult felt tacked on, making for a poor coda to the vital tale of her childhood, never mind an adolescence that was skimmed over almost entirely. I also had a hard time figuring out whether or not she was castigating Chinese culture for some of the truly awful things that were taught to her — I’d like to think she was rebuking them, but the tone was uncertain, as if she feared that saying as much meant she was betraying her heritage.

But, you know, any book that seeks to lance the weird apathy, if not downright hostility, large swathes of America feel on the subject of “illegal” immigration is a good thing. It takes a lot of courage to admit to the trauma and shame of your past, and Ms Wang certainly does her best to present her experience with honesty. Hopefully, her efforts will encourage the rest of us to keep working towards a world that is more just and kind to people who are looking only to work without exploitation, and hence perhaps to fit in and give back to the communities where they find themselves.

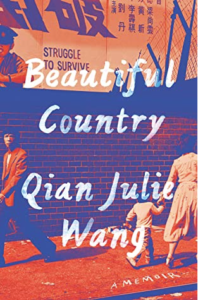

Beautiful Country: A Memoir by Qian Julie Wang was published September 7 2021 by Doubleday Books and is available from all good booksellers, including