The problem with telling a story, of course, is that you already know that I’m telling you about something significant that happened. It’s not as if we sat down together and you said, “Alex, tell me a tale where you had a pleasant trip to your homeland and the worst menace you faced was the amount of paprika the Widow put in the sausages.” No, you wanted a proper hair-raiser and here I am, trying to tell you one, whoever you are. (p. 69)

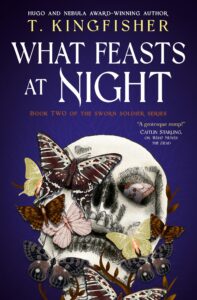

Alex Easton, sworn soldier of Gallacia and first-person narrator of What Feasts as Night as well as What Moves the Dead, delivers that meditation about halfway through the novella, when they are well past the unpleasant trip part and my hairs, at least, were rising in alarm.

Easton and their* batsman Angus have left the delights of Paris for the dank, dark days of a rural Gallacian autumn. Miss Eugenia Potter, an Englishwoman and noted mycologist who attracts adjectives like “redoubtable,” provided crucial advice and support during the events chronicled in What Moves the Dead. The climate of Gallacia being particularly suitable for many types of fungus, Easton has offered Miss Potter the use of a family hunting lodge as a base for a period of research. Angus and Easton have come back from Paris to serve as translators and cultural interpreters. One problem has already arisen even before any of them arrive.

It seems that Codrin, the caretaker of a hunting lodge that Easton inherited, had not answered their letters for months. That’s out of character, and alarming enough that Easton is glad to be making a personal visit to sort out the situation. Years ago, when Easton had recently returned, shattered, from the wars, Codrin’s stoic kindness helped them return to the world in something approaching a healthy state of mind. Since then, he had been more than a family retainer inherited from a previous era.

Easton’s premonition proves all too warranted: Codrin has died, and the townspeople are unusually closed-mouthed about the circumstances of his death. Hiring a new caretaker proves all but impossible. Angus eventually finds both a new person to look after them and the lodge, and what people think happened to Codrin. Easton knows the lingering power of folk belief in rural Gallacia, “But still, a fairy-tale woman that sits on your chest? Really?” (p. 36) Easton is more enthusiastic about the Widow Botezatu — a woman with “knuckles like old mortar shells and a nose with a sharp red tip” — who brings her grandson Bors along for additional help.

He was a large, amiable young man who chopped firewood and milked goats and lifted heavy objects with one hand. When you talked to Bors for very long, you realized that he was slow, and if I had meant stupid I would have said that instead. Bors had a mind like a lava flow. It took a long time to get where it was going, but there was no stopping it. I quite liked him. (p. 56)

All would seem to be well for mycological research for Miss Potter and a little light rustication for Easton, except that both they and Bors start to show some of the symptoms that Cordin exhibited. Nor is medical attention always welcome in a place where folk remedies are held in far more esteem than science.

“I wouldn’t worry about tuberculosis unless it goes on for another few weeks,” Dr. Virtanen [who is from Finland] murmured in an undertone. “But if [Bors] starts coughing more, or coughing up blood, call for me at once. Odds are good it’s nothing more than a passing infection of the lungs, but there’s always a chance …” He spread his hands.

“I doubt Mrs. Botezatu will let us send for you,” I said glumly. “She thinks doctors are a type of undertaker.”

He smiled ruefully. “A common enough belief locally. Worse if one is a foreigner. Though you might consider building a sauna. It won’t hurt, and even if it doesn’t help, at least then you’ll have a sauna.”

Which, as medical advice goes, was not the worst I’d ever heard by a long shot. (p. 101)

At the border between medicine and superstition, between science and the supernatural, What Feasts at Night is mostly a study of character. Nobody wants anyone to get any sicker, but their competing ideas about the causes lead them to take conflicting actions to keep illness at bay. Sometimes when Easton bends to the requirements of local wisdom they only seem to make the situation worse. The Widow, too, appears to bend, but with the life of her beloved grandson on the line, she is prepared to take desperate action.

The novella length is just right; this hair-raiser is only about one thing, and trying to stuff more in would have diluted its creepy power. The resolution comes as a breath of fresh air, a break in the dimming days of the Gallician autumn. I should go back and check whether Easton got a sauna out of it, too.

+++

* Gallacian has a surprising number of pronouns, including those that apply only to soldiers, and within the story Kingfisher applies those to Easton. Outside of the story, they/their is less confusing, and Kingfisher also follows this practice on the book’s cover copy.

1 ping

[…] Kingfisher’s third Sworn Soldier novella — following What Moves the Dead and What Feasts at Night — takes Alex Easton and their* batsman Angus to America at the urgent behest of their friend […]