Charlie Fitzer’s day is just about to get a lot better. As it begins, he’s divorced (his ex-wife is seeing an investment banker and sharing her fabulous vacations on her Instagram account, which of course Charlie follows), his career has descended from business reporter for the Chicago Tribune to middle-school substitute teacher (thanks to layoffs and a stint caring for his father during his final illness), his bank account is near zero and his main asset is a quarter share of his childhood home, where he has continued to live after his father’s death. His three half-siblings, holders of the other shares, very much want to sell. Then Charlie gets news that his uncle has died. His billionaire uncle. Who had no other close relatives. Also, a kitten adopts Charlie.

His week, however, is just about to get a lot worse. The first real inkling of how bad is when one of the mourners at his uncle’s funeral pulls out a big knife and winds up to stab the corpse. This is how it came to pass: One of his uncle’s minions showed up at Charlie’s house (“He kept tabs on you,” [Mathilda] Morrison [the minion] said. “Discreetly. From a distance. In a way that wouldn’t antagonize your father.” “Well, that doesn’t sound creepy at all,” I said. (p. 25)) and offered to set up a deal that would leave Charlie sole owner of the house and give him enough money to become proprietor of the local pub, something he felt would be much better than substitute teaching. The catch was that he would have to stand for his uncle at the funeral a few days later. Stabbing had not been mentioned in advance. That this might not be an ordinary funeral was indicated by floral arrangements delivered by courier bearing messages such as “See you in Hell” (“It is, however, one of the nicer [messages].” (p. 34)) and “Not soon enough.” Then there were the mourners.

[They] were exclusively male, in their late thirties to early forties. They all stood in a manner that suggested that at some point in their lives they had spent a lot of their time at parade rest.

The men arrived mostly in pairs or trios, and kept to their own groups, with little to no cross-conversation. What conversation was being had was kept low and murmuring. Every once in a while one or two of the men would glance briefly at me and then look at something else. I was being noted and registered.

None of the men went out of their way to offer me condolences, or to speak to me about my uncle, or the service, or, well, anything.

They were all just … waiting.

The director of the funeral home, by the way, is a lovely minor character. Mr Chesterfield — the name is not just a style of furniture but also one of The Penguin’s middle names — is a font of deadpan politeness and tact, though Scalzi allows him flashes of wicked humor.

“At least this [condolence message] isn’t one hundred percent awful,” [said Charlie.]

“It’s not, but it seems to suggest the sender is not entirely convinced your uncle has passed on,” Chesterfield said.

“Has he?”

“Passed on?”

“Yes.”

“He was dead when he arrived here,” Chesterfield said.

“Do you expect that condition to change?”

“It would be unusual if it did.” (pp. 35–36)

Anyway. Charlie. Uncle, dead in coffin. Mourners, or at least visitors. And then suddenly: knife.

I yelled and launched myself at the stabber. Almost immediately, and yet too late, I realized that was a not-at-all smart thing to do. The stabber was taller and more muscular than I was, and had the sort of close-cropped hair and almost-fashionable stubble that made me think of some of the more active yet less legitimate secret services out in the world. I pushed this man, and as I did I had the terrible sense that the man was deciding whether or not to allow himself to be pushed, or to deflect me and drive me into the carpet.

That infinitesimal moment lasted forever. Then the stabber chose to let himself be pushed. (p. 42)

Altercation averted, Charlie learns that none of the mourners had actually known his uncle. They are all representing their bosses to ensure that Uncle Jake is dead, by taking direct action if necessary. It’s not personal, they say, just business. When it is established that Charlie’s uncle is in fact as dead as the proverbial doornail, they leave promptly. After a few more friendly words with Chesterfield, Charlie heads home.

His cats greet him as he’s across the street from his house, and he pauses for a moment. Which is good for Charlie because just at that instant the house explodes all over the street.

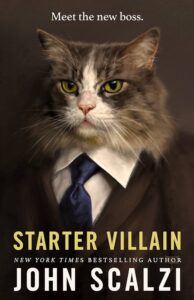

It’s he first of several well-timed explosions in Starter Villain. The book is written with such glee that I wonder whether Scalzi got to certain parts of the story and thought to himself, “Let’s blow something up and see what happens.” The first explosion leaves Charlie homeless, nearly penniless and, as the lawyer for his father’s estate is quick to point out, soon to be a suspect for arson. Hilarity ensues.

Astute readers, including any who have read the back cover or dust-jacket flap, will be several steps ahead of Charlie. His late and only somewhat lamented Uncle Jake may have made billions in the parking garage business, but he made much more pursuing his true calling as a supervillain, complete with volcanic island lair. By standing for his uncle at the funeral, he has placed himself in his uncle’s stead, at least as far as his fellow villains are concerned. They’re the bosses who sent the lovely parting messages, and the menacing mourners. And they’re more than concerned, they’re interested, as the fate of Charlie’s house demonstrated.

Readers being slightly ahead of Charlie is part of why Starter Villain works so well. Often enough, I could see what Charlie was headed toward, and I couldn’t wait to find out. Other times, I was just as surprised as he was, and not all of those surprises involved explosions. Scalzi’s in total command of his novel’s pace, and most of the time it’s somewhere between madcap and frenetic. Because of course the logical thing to happen next after his house gets blown up is for Charlie to get a phone call from his uncle’s minion who tells him to follow his cats.

“What?”

“Follow your cats,” Morrison repeated.

“What is that supposed to mean?”

“What part of ‘follow your cats’ is hard to understand?” Morrison asked.

“All of it, honestly,” I said.

“Look, don’t overthink it, Charlie,” Morrison said. “Tell Hera I told you to follow her. She’ll take it from there. I’ll see you later tonight. We have things to discuss.” She hung up. (p. 54)

It doesn’t slow down for another two hundred or so pages, and it only does so then because most of the last chapter is cleaning up afterward. I got there in three sittings, but if I had started earlier in the day it might have been two or even one. For people taking a slower or more old-fashioned approach, Scalzi obliges with a kicker or a cliffhanger at the end of each chapter. Chapter 7, for example:

“Yes,” [said Morrison] “After we visit the volcano lair. We have some business there first.”

“Volcano lair,” I repeated.

“There’s a good reason why we have one. It’s not just for show.”

I looked back at Hera [his cat]. She slow-blinked at me.

“So,” Morrison said. “You want in?” (p. 68)

And on this turbocharged ride, I laughed so much. So, so much. Some writers of science fiction comedy do it by piling on improbabilities, by adding details and drollery; Catherynne Valente and Douglas Adams are two in this category. Terry Pratchett wrote punny sentences, hilarious set pieces, and great human comedy across entire groups of novels. In Starter Villain, Scalzi’s comedy works by taking out almost everything else. There’s just enough description to establish a scene, but almost all of the business of the book is done by what the characters say. Readers get to imagine the characters’ movements and expressions, whether they’re deadpan or over the top, because the humor works either way. Real-life negotiations aren’t conducted with as much zip and verve, and that’s fine; Elizabethan princes didn’t declaim in iambic pentameter.

It also works because Charlie is an everyman dropped into a series of increasingly strange situations. Confronted with crazypants, he doubles the humor by holding on to normality. He’s not as hapless as Arthur Dent, but he’s not nearly hapful enough to take command of events, and most of the time he knows it. He also startles people at the volcano island lair by doing the basically decent thing as, for example, when he recognizes the dolphins’ newly formed labor union. Sometimes that gives him a leg up on his counterparts in the villain business, since they are used to treachery and conniving.

But sometimes it just invites more explosions.

+++

Starter Villain was the first work I read as part of voting in the 2024 Hugo Awards, and it is the first I have written about.

1 pings

[…] about the finalists, even if I have already read some of the other nominated works. (And I read Starter Villain so fast and with such delight that I couldn’t not write about it.) So here are my brief […]