One of the ways that the Folly — the secret unit of London’s Metropolitan Police Service that deals with the supernatural — is integrated into regular police work is that they receive reports concerning missing children. Apparently in previous eras, rogue practitioners used to use children for some very rogue practices. And so Nightingale dispatches Peter to fictional Rushpool in not-entirely-fictional Herefordshire on the English-Welsh border to lend a hand to the local police in the disappearance of two eleven-year-old girls.

Nightingale explains:

“… It’s always been our policy to keep an eye on missing child cases and, where necessary, check to make sure that certain individuals in the proximity are not involved.”

“Certain individuals?” I asked.

“Hedge wizards and the like,” he said.

In Folly parlance a “hedge wizard” was any magical practitioner who had either picked up their skills ad hoc from outside the Folly or who had retired to seclusion in the countryside—what Nightingale called “rusticated.” (p.5)

Nightingale has someone in particular in mind.

I popped back to the Folly proper and met Nightingale in the main library where he handed me a manila folder tied up with red ribbons. Inside were about thirty pages of tissue-thin paper covered in densely typed text and what was obviously a photostat of an identity document of some sort.

“Hugh Oswald,” said Nightingale. “Fought at Antwerp and Ettersberg [the WWII clash between British and German magicians that left few alive on either side].”

“He survived Ettersberg?”

Nightingale looked away. “He made it back to England,” he said. “But he suffered from what I’m told is now called post-traumatic stress disorder. Still lives on a medical pension—took up beekeeping.”

“How strong is he?”

“Well, you wouldn’t want to test him,” said Nightingale. “But I suspect he’s out of practice.”

“And if I suspect something?”

“Keep it to yourself, make a discreet withdrawal and telephone me at the first opportunity,” he said. (pp. 6–7)

Right away, Peter has a part in an urgent case — the British media have caught wind of the disappearance are about to descend on Rushpool — and a magical someone who may or may not be involved. After a slightly unsettling interview with Hugh Oswald, and his granddaughter, and some Australians working at Oswald’s buzzing tower, Peter makes his way to the police station closest to the disappearance and is assigned to work with Detective Sergeant Dominic Croft. He grew up in the area and is Peter’s — and readers’ — guide to local history, connections, and shortcuts. He has the usual questions for Peter, too.

“There’s weird shit,” I said. “And we deal with the weird shit, but normally it turns out that there’s a perfectly rational explanation.” Which is often that a wizard did it.

“What about aliens?” asked Dominic.

Thank god for aliens, I thought, muddying the waters since 1947. I’d once asked Nightingale the same question and he’d answered, “Not yet.” …

“Not that I know about,” I said. (pp. 30–31)

Which Aaronovitch leaves up in the air as a running theme develops later in Foxglove Summer that the area is a hotbed of alien sightings. He also pokes fun at how modern management jargon has crept into policing. The book has chapter titles such as “Customer Facing,” “Intelligence Led,” and, at the end, “Going Forward.” Not too terribly many pages after Peter has opined that bureaucratic language, especially when liberally applied, is a lovely way to produce many words without adding any meaning at all he tells one of the area’s genius loci that “Stakeholder engagement is a vital part of our modernization plans going forward.” (p. 99) Late in the book, Peter catches a ride in a car with a surprisingly good stereo system, but the only CD available is Queen’s Greatest Hits, which I took as a reference to Good Omens and the unfortunate tendency of any cassette in the demon Crowley’s car to transmogrify into that album.

Meta jokes aside, Foxglove Summer is a good Rivers of London story transported to the countryside. Aaronovitch is good about some of the tensions in a rural county, with some people having been there since time immemorial and others having only having moved there once they had enough money not to have to do any agricultural work. He also tells when some people think that “time immemorial” is about a dozen years. The local eateries have almost all gotten very precious about the descriptions on their menus, especially when Peter just wants something fried and reliably awful. Aaronovitch is further good about some of the difficulties of policing in an area where nearly everyone has known everyone since they were small. Interpersonal relations can be both tangled and thorny, and crucial because two little girls are missing and presumed endangered.

The case gets considerably more complicated before it gets solved. Well, mostly solved, because one of the other things that Aaronovitch is good about across the series is neither tidying up all of the details in the end nor making magic so systematic that it loses its mystery or unpredictability. Peter learns more about the history of the Folly and gains some insight into magic outside his beloved London, but at the end he’s also happy to return to familiar haunts. Even though some of the loose threads he left behind in the capital may have become a web or a rope by the time he gets back, but that is for me to find out in future volumes.

+++

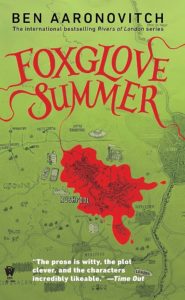

Doreen’s review of Foxglove Summer is here.

1 pings

[…] for his official view, he gives another flash of the bureaucratic jargon so lovingly mentioned in Foxglove Summer: “We at the Folly have embraced the potentialities of modern policing.” (p. […]