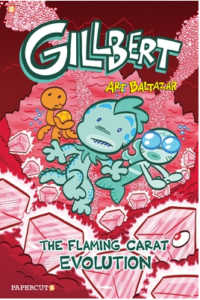

I got my 9 year-old to do a buddy read on this one with me, and he definitely liked it a little more than I did, story-wise, at least. We both greatly enjoyed Art Baltazar’s delightfully rounded, pastel-hued art, which blends alien action with underwater adventure in a kid-friendly and -accessible way. This is the creative genius behind Young Justice and Tiny Titans, after all, so his art is going to have lots of wide-ranging appeal.

Where Jms’ and my opinions diverged was on the story, which is basically this: Gillbert is the heir to the kingdom of Atlanticus, and with assorted family and friends must deal with a new threat brought about by the ongoing evolution of the evil alien Pyrockians. Gillbert’s circle of friends is vastly enlarged when Anne Phibian takes him home to meet her family, who want to inspect this boy she’s been spending so much time with. It’ll take all our heroes’ connections — underwater, on land and in space — to foil the Pyrockians’ evil plans.

Where Jms’ and my opinions diverged was on the story, which is basically this: Gillbert is the heir to the kingdom of Atlanticus, and with assorted family and friends must deal with a new threat brought about by the ongoing evolution of the evil alien Pyrockians. Gillbert’s circle of friends is vastly enlarged when Anne Phibian takes him home to meet her family, who want to inspect this boy she’s been spending so much time with. It’ll take all our heroes’ connections — underwater, on land and in space — to foil the Pyrockians’ evil plans.

Personally, I thought the story quite slight for the number of pages, especially since a good part of it was spent recapping the cast and how they’d been introduced in the past two books. That was actually Jms’ favorite part of the volume tho, getting to know all the characters. We did both appreciate the not too heavy-handed message about love saving the day in the end.

Tonally, everything reminded me very much of a Hellboy-lite, unsurprising given Mr Baltazar’s previous experience on Itty Bitty Hellboy. The banter between the characters was nice, but I still don’t understand how the Phibians knew the Pyrockians were behind the initial sign of underwater disturbance. Jms seemed satisfied with the story, tho, and since he’s part of the book’s target demographic of middle-grade readers, I suppose that’s more important than my own satisfaction.