Q: Every book has its own story about how it came to be conceived and written as it did. How did A Breath After Drowning evolve?

A: I was haunted by the image of a mother abandoning her daughter in the waiting room of a psychiatric hospital—silver crosses draped around the young girl’s neck and rosaries wrapped around her wrists. Why? How could a mother abandon her child like that? I became obsessed with this betrayal, and it ignited my imagination.

Q: You’ve said on your website that “Dreams inspire writing.” How did you learn to translate the ephemera of dreams into the (relative) concrete of words when you were first starting?

A: Each one of my novels was inspired by a dream. Before I wrote “A Breath After Drowning,” I had a dream that my husband and I came home and couldn’t get our front door open. I slid the key into the lock but it wouldn’t turn. Inside, the phone was ringing off the hook, and I knew in my heart something horrible had happened. That dream was the seed that grew into my new novel.

Q: I really took to heart your words on How To Be A Writer, one of the first blog posts on your website. I would probably do better myself for spending less time on the Internet. Do you adhere to any particular writing regimen, disconnecting aside?

A: I wake up at four or five in the morning. There’s a narrow window of time and mood that opens and I need to jump through it or it might close again. So I sit down at my desk and start writing. If I get stuck, I follow Ernest Hemingway’s advice: “Write the truest thing you know.” That always works for me.

Q: Aside from writing thriller novels, you’ve also won awards for your short stories. I love your quote on marrying the sweeping scope of thrillers with the personal epiphanies of short stories in your fiction. Do you ever find yourself preferring writing one form to the other?

A: I love them both equally. But there are fundamental differences—in the short story, I’m examining my main character’s most profound moment through a microscope. With novels, I’m viewing an entire galaxy through a telescope.

Q: We usually like to ask whether an author is a pantser (someone who writes by the seat of their pants) or a plotter, but I imagine that, in order to write any sort of mystery novel convincingly, you have to plot heavily. Did you find yourself surprised, however, by any unexpected directions in the plot in A Breath After Drowning took outside of what you’d planned?

A: I’m both. I write an outline, but I love being surprised by what organically happens, as well. For example, in “A Breath After Drowning,” I’d planned early on for one of my characters to be deeply evil. But then, months later, another character became the villain. I love when that happens, and it happens all the time. In truth, writing fiction is a profoundly mysterious process.

Q: A Breath After Drowning provides an intimate look at the mental health care system from intake to outpatient, historical to present, especially for troubled adolescents. I was impressed by your research on the subject, and am curious as to your opinion of the state of mental health care in America today.

A: Allow me to answer that question more personally. My father was bipolar, and growing up with that was like riding an emotional roller coaster. It has affected my entire life and informs everything I write. But there are good therapists out there who can guide you through the pain and turmoil.

Q: What is the first book you read that made you think, “I have got to write something like this someday!”

A: “The Wolves of Willoughby Chase” by Joan Aiken. It inspired me to write my first novel when I was seven years old. It was a murder mystery, and it began, “It was a rainy day in Lond, England. It was raining halfway up to my ankles.” LOL.

Q: What can you tell us about your next project?

A: I’m writing a witchcraft thriller.

Q: Tell us why you love your book!

A: I love the nasty dark bristles of evil juxtaposed against innocence.

~~~

Author Links:

AliceBlanchard.com

~~~

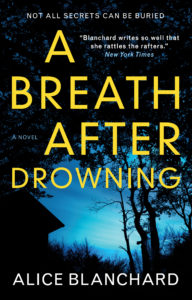

A Breath After Drowning was published on April 10th 2018 by Titan Press and is available through all good book sellers. My review of the book itself is here.