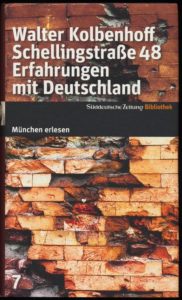

For all that it is a Millionenstadt, Munich can also be quite a small town. Literary and artistic Munich even more so. Thus it’s not very surprising that in Schellingstrasse 48 (48 Schelling St.), Walter Kolbenhoff’s memoir of the Nazi era, POW internment in America, and early post-war Munich, other authors from the Süddeutsche Zeitung‘s series of 20 books about Munich make appearances. Oskar Maria Graf, whose Der ewige Spiesser followed two books after Wir sind Gefangene came two books before Kolbenhoff’s in the series, was an occasional visitor to Schellingstrasse. Kolbenhoff uses a well-known phrase from Thomas Mann that the Süddeutsche later used as the title for the Mann volume in the series. Alfred Andersch, author of Der Vater eines Mörders was in the same POW camps as Kolbenhoff in Louisiana and Pennsylvania; they were both involved in a POW publication called Der Ruf as well as a successor of the same name published in Munich after the war; later they were both involved in early post-war West Germany’s most important literary movement, Gruppe 47. In short: Munich connected.

Kolbenhoff himself was surprised to wind up in Munich. He was a Berliner born and bred. As a young apprentice, he wandered far and wide in Europe, the Middle East, and North Africa. He felt drawn to southern lands. He returned to Berlin, but the advent of Nazi power forced him into exile, and he landed in Copenhagen. That city welcomed him, and he felt at home there, learning Danish and plying various trades until the war took an interest in him. After his release from American internment, he fully intended to return there. Chance, in the form of a letter from a fellow prisoner to his family in rural Bavaria, took Kolbenhoff to southern Germany. The family turned out to be local gentry, and at a time when meager rations made malnutrition a common experience in German cities, Kolbenhoff found himself living well as a practical adoptee of well-off farmers. In the bitter months of 1946, he was warm and well fed. The war seemed hardly to have touched Bad Aibling.

Nevertheless, errands take him into the big city. Munich is in ruins, former soldiers are everywhere scrounging food and cigarettes, “women in worn-out dresses and coats. The faces were without expression, the eyes cast down and without the slightest emotion. I saw no children. I was seized by an uncanny loneliness and despair. Get out of this city, just get out!” (p. 16, my translations throughout) A few steps later, though, he sees a notice — “All book printers, typesetters, letter-makers, book binders, etc. report to Alfred Andersch, Schellingstrasse 39.” (p. 16) — and resolves to check whether it is his old friend with the unusual name. It is indeed, and Andersch has landed at a newspaper approved and supplied by the US occupation authorities. By the end of the afternoon, Kolbenhoff has a job at the paper, has met the renowned author Erich Kästner, and has a line on one of the rarest goods in Munich: an intact dwelling. “‘What a day,’ [in English in the original] I thought when I stood outside [of the newspaper offices] on Schellingstrasse again.” (p. 22)

So it proves. Kolbenhoff trades his idle rural idyll for the busy life of a roving reporter, at first in and around Munich, and then across post-war Germany. “Go find things to write about,” his editor tells him, “and come back and write about them.”

Writing nearly 40 years later, Kolbenhoff captures the gray desperation of Germany soon after the end of the war. Streets can barely be found amid the rubble strategic bombing had made of Munich. Vehicles run, irregularly, on unorthodox fuels. When, late in the book, a group of writers venture out to Füssen to start what will become Gruppe 47 the trains only run halfway, about 60 kilometers. They find space in the back of an open truck for the rest of the journey; on arrival, they strip down and jump in a lake to remove the soot accumulated on the trip. Nearly a year and a half after war’s end there are three train connections from Munich to Berlin. Travel time is 28 hours. (Today’s fastest trains make the same trip in just under four hours.)

He also captures the excitement of building something new, of democratic opportunities that are now available, of what some hoped that Germany could become without the shackles of either feudalism or dictatorship. The newspaper job soon gave him enough pull that he was allowed to rent an apartment in newly reconstructed floors of a building — the eponymous Schellingstrasse 48 — not far from the paper’s offices. It becomes a natural meeting point for writers, journalists, and other interesting people either living in Munich or passing through for one reason or another.

Kolbenhoff intersperses his narrative of post-war Munich with details of how he got there. He grew up working-class in a staunchly social democratic (SPD) household. As an impatient young man in the 1920s he found his father’s SPD stodgy and ineffective. He joined the Communists and made a bit of a name for himself as a writer and editor for the Party newspaper. The night of the Reichstag fire, he gets off the train a stop earlier than usual and walks toward his home by a different route. A friendly neighbor tips him off that the Gestapo is waiting. Saved, he sleeps rough for a couple of nights and makes his way to Amsterdam. The Dutch are not keen on refugees who could draw hostile attention from their large neighbor, and Kolbenhoff winds up in custody. A lucky intervention sees the Dutch putting him on the next ship rather than just across the border into Germany. Not that the ship takes him far, its destination is Copenhagen. The Danes, however, do not see the need to deport him, and he stays for nearly a decade, learning Danish, meeting Wilhelm Reich, writing a book that gets him expelled from the Communist Party, and eventually getting scooped up by the Wehrmacht.

He has the good fortune to be captured by the Americans. The first POW camp that Kolbenhoff describes is just outside of Ruston, Louisiana. (Tauben im Gras has several connections to Baton Rouge, Louisiana, where I grew up. I don’t know quite what to say about seeing 1940s Louisiana reflected in the imagination and recollection of German authors writing about their post-war experiences, other than that it is very odd.) Later, Kolbenhoff is transferred to another camp where the American army is collecting anti-Nazi Germans with an aim to seeding a more democratic post-war Germany.

Kolbenhoff reflects on how all of the pieces fit together. “For the first time in many years I had, at Schellingstrasse 48, once again found a home in Germany, with many friends and acquaintances who came and went. While I wrote and looked back at the Schellingstrasse, other people and events that lay further back came to life for me again. In this fashion, Schellingstrasse 48 became a sort of kaleidoscope, in which recollections like slivers of glass re-arranged themselves continuously into new images.” (p. 231)

The great strength of the book is that the images and incidents that Kolbenhoff calls back to life are as colorful and vivid as what a kaleidoscope shows, whether it’s the black-market profiteer on that first day in Munich, or the prisoners’ efforts to smuggle their pets into the next POW camp, or the literary meeting that captures everyone’s imaginations, or any other scene from this slight but affecting volume. The years between the war and the economic miracle are increasingly lost to memory as they recede further into history. Kolbenhoff’s book returns that time to life, reminding readers of how cold, poor and ruined Germany was, how uncertain their future was.