Becoming really is that good. Here’s a lengthy excerpt from the beginning.

There’s a lot I still don’t know about America, about life, about what the future might bring. But I do know myself. My father, Fraser, taught me to work hard, laugh often, and keep my word. My mother, Marian, showed me how to think for myself and to use my voice. Together, in our cramped apartment on the South Side of Chicago, they helped me see the value in our story, in my story, in the larger story of our country. Even when it’s not pretty or perfect. Even when it’s more real than you want it to be. Your story is what you have, what you will always have. It is something to own.

For eight years, I lived in the White House, a place with more stairs than I can count—plus elevators, a bowling alley, and an in-house florist. … Our meals were cooked by a team of world-class chefs and delivered by professionals more highly trained than those at any five-star restaurant or hotel. Secret service agents, with their earpieces and guns and deliberately flat expressions, stood outside our doors, doing their best to stay out of our family’s private life. We got used to it, eventually, sort of—the strange grandeur of our new home and also the constant, quiet presence of others.

The White House is where our two girls played ball in the hallways and climbed trees on the South Lawn. It’s where Barack sat up late at night, poring over briefings and drafts of speeches in the Treaty Room, and where Sunny, one of our dogs, sometimes pooped on the rug. … There were days when I felt suffocated by the fact that our windows had to be kept shut for security, that I couldn’t get some fresh air without causing a fuss. There were other times when I’d be awestruck by the white magnolias blooming outside, the everyday bustle of government business, the majesty of a military welcome. There were days, weeks, and months when I hated politics. And there were moments when the beauty of this country and its people so overwhelmed me that I couldn’t speak.

Then it was over. … And when it ends, when you walk out the door that last time from the world’s most famous address, you’re left in many ways to find yourself again.

So let me start here, with a small thing that happened not long ago. I was at home in the redbrick house that my family recently moved into. Our new house was about two miles from our old house, in a quiet neighborhood street. We’re still settling in. In the family room, our furniture is arranged the same way it was in the White House. We’ve got mementos around the house that remind us it was all real—photos of our family time at Camp David, handmade pots given to me by Native American students, a book signed by Nelson Mandela. What was strange about this night was that everyone was gone. Barack was traveling. Sasha was out with friends. Malia’s been living and working in New York, finishing out her gap year before college. It was just me, our two dogs, and a silent, empty house like I haven’t known in eight years.

And I was hungry. I walked down the stairs from our bedroom with the dogs following on my heels. In the kitchen, I opened the fridge. I found a loaf of bread, took out two pieces, and laid them in the toaster oven. I opened a cabinet and got out a plate. I know it’s a weird thing to say, but to take a plate from a shelf in the kitchen without anyone first insisting that they get it for me, to stand by myself watching bread turn brown in the toaster, feels as close to a return to my old life as I’ve come. Or maybe it’s my new life just beginning to announce itself.

In the end, I didn’t just make toast. I made cheese toast, moving my slices of bread to the microwave and melting a fat mess of gooey cheddar between them. I then carried my plate outside to the backyard. I didn’t have to tell anyone I was going. I just went. I was in bare feet, wearing a pair of shorts. … I sat on the steps of our veranda, feeling the warmth of the day’s sun still caught in the slate beneath my feet. A dog started barking in the distance, and my own dogs paused to listen, seeming momentarily confused. It occurred to me that it was a jarring sound for then, given that we didn’t have neighbors, let along neighbor dogs, at the White House. For them, all this was new. As the dogs loped off to explore the perimeter of the yard, I ate my toast in the dark, feeling alone in the best possible way. My mind wasn’t on the group of guards with guns sitting less than a hundred yards away at the custom-built command post inside our garage, or the fact that I still can’t walk down a street without a security detail. I wasn’t thinking about the new president or for that matter the old president, either.

I was thinking about how in a few minutes I would go back inside my house, wash my plate in the sink, and head up to bed, maybe opening a window so I could feel the spring air—how glorious that would be. I was thinking, too, that the stillness was affording me the first real opportunity to reflect. As First Lady, I’d get to the end of a busy week and need to be reminded of how it started. But time is beginning to feel different. My girls, who arrived at the White House with their Polly Pockets, with a blanket named Blankie, and a stuffed tiger named Tiger, are now teenagers, young women with plans and voices of their own. My husband is making his own adjustments to life after the White House, catching his own breath. And here I am, in this new place, with a lot I want to say. (pp. x–xiii)

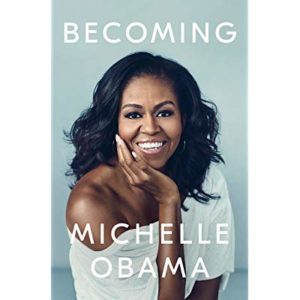

There she is, and she does. This is Michelle’s story (I will use first names to distinguish the Obamas), as the cover without the word “by” on it implies by omission: Becoming Michelle Obama. Barack, without whom this book would not exist, is mostly off-stage, observed, loved, but shown at a certain distance. She thinks he’s the bee’s knees, and also sometimes exasperating. As she writes later on, “All [Barack’s] inborn confidence was admirable, of course, but honestly, try living with it.” (p. 131)

The preface sets the stage for Michelle to sit down and tell the reader her story. It’s a friendly invitation, just finishing some cheese toast and sitting down on a spring evening, alone with the reader (or listener; I am told that the audio version that she narrates herself is terrific), ready to talk for a good long while about who she is, where she came from, how she came to be where she just was. None of this is accidental; Michelle will say numerous times later in the book that she is a planner, a detail person. Becoming is a finely honed work from a graduate of Princeton and Harvard Law who has learned how to marshal considerable resources to communicate what she wants to get across, and to do that on several levels at once. Like Barack did with Dreams From My Father, Michelle has thought long and clearly about why people want to read her first book. Compared with her husband’s first effort at book-length writing, she brings nearly twenty years more of life experience, as well as time in the White House crafting messages, to the task, and it shows. (Charmingly, Dreams From My Father was written in part to impress Michelle; Becoming was not written to impress Barack, but it is by far the more polished of the two books.)

She divides the book into three parts: Becoming Me, Becoming Us, and Becoming More. She leaves the ending open; to paraphrase the father of one of her childhood friends, life is not finished with her yet. “I’m an ordinary person who found herself on an extraordinary journey. In sharing my story, I hope to create space for other stories and other voices, to widen the pathway for who belongs and why. … For every door that’s been opened to me, I’ve tried to open my door to others. And here is what I have to say, finally: Let’s invite one another in.” (pp. 420–21) She invites readers into her life to show how ordinary it was, how easily she might have tripped over obstacles she barely even knew were there, and how someone from a modest South Side upbringing has handled being catapulted onto the world stage, and indelibly into history.

She also lets readers know that she and her family had been part of history all along, just not at the rarefied level of the White House. She grew up on the South Side of Chicago amid an extended family on both sides, with parents who had grown up in the city themselves but a grandparents’ generation that had come up from the South as part of the Great Migration. The South Side did not stand still either; as she writes in the caption accompanying two photographs, “When I began kindergarten in 1969, my neighborhood on the South Side of Chicago was made up of a racially diverse mix of middle-class families. But as many better-off families moved to the suburbs—a phenomenon commonly known as “white flight”—the demographics changed fast. By fifth grade, the diversity was gone.” (color photos after p. 240) She describes a visit to friends who had moved out to the suburbs, a very light-skinned African-American family. While Michelle, her brother, and her parents were inside the friends’ house visiting and having dinner, someone keyed a panel of the Buick that was her father’s pride and joy. Nobody in the family said much about the incident, and her father had it repaired within the week, but they did not visit again and never considered moving out of the city.

Every phase that she chooses to describe is a rich tapestry. There’s a beloved grandfather with his record collection who introduces her to jazz. There’s her mother’s forthright action that saved her from a terrible second-grade teacher and set her on an academic path that led to Princeton and Harvard. There’s her big brother, always looking after her, and later providing a path to the scarily exciting world of boys. There’s her friendship with Santita Jackson, daughter of Rev. Jesse. There’s the fearsome aunt who taught her piano and also unintentionally gave her lessons in standing up for herself. All of these and more that were interesting, touching, enlightening, and all from before her graduation from high school. She did well enough to earn a place at Princeton, a college that she found thrilling, sometimes intimidating, and sometimes confining. She also found it very, very white.

I imagine that the administrators at Princeton didn’t love the fact that students of color largely stuck together. The hope was that all of us would mingle in heterogeneous harmony, deepening the quality of student life across the board. It’s a worthy goal. … But even today, with white students continuing to outnumber students of color on college campuses, the burden of assimilation is put largely on the shoulders of minority students. In my experience, it’s a lot to ask. (p. 74)

Princeton also introduced her to friends who would be important to her long after graduation, such as Suzanne Alele, whom she had met during a pre-first-year program. They were more complementary than identical, as they discovered when they started sharing a room as sophomores. “Our shared room resembled an ideological battlefield, with Suzanne presiding over a wrecked landscape of tossed clothing and strewn papers on the floor on her side and me perched on my bed, surrounded by fastidious order. … I see now that she provoked me in a good way, introducing me to the idea that not everyone needs to have their file folders labeled and alphabetized, or even to have files at all. Years later, I’d fall in love with a guy who, like Suzanne, stored his belonging in heaps and felt no compunction, really ever, to fold his clothes. But I was able to coexist with it, thanks to Suzanne. I am still coexisting with that guy to this day. This is what a control freak learns inside the compressed otherworld of college, maybe above all else: There are simply other ways of being.” (pp. 80–81) Princeton shaped her—there are more Suzannes than I can mention here—and it gets the better part of two chapters.

She dispenses with Harvard Law in about two paragraphs, mostly in a discussion about how she had grown up checking off boxes and seeking approval that leads to both awe and chagrin at having made it by her mid-20s. “You used to pass by [the office building where you now work as a lawyer] as a South Side kid riding the bus to high school, peering mutely out the window at the people who strode like titans to their jobs. Now you’re one of them. You’ve worked yourself out of that bus and across the plaza and onto an upward-moving elevator so silent it seems to glide. You’ve joined the tribe. At the age of twenty-five, you have an assistant. You make more money than your parents ever have. … You wear an Armani suit and sign up for a subscription wine service. You make monthly payments on your law school loans and go to step aerobics after work. Because you can, you buy yourself a Saab.” (p. 92)

She’s well aware of how fortunate she is, and how many people supported along the way. She’s not aware—how could she be—of what’s about to happen.

Is there anything to question? It doesn’t seem that way. You’re a lawyer now. You’ve taken everything ever given to you—the love of your parents, the faith of your teachers, the music from Southside [a grandfather’s nickname] and Robbie, the meals from Aunt Sis, the vocabulary words drilled into you by Dandy—and converted it to this. You’ve climbed the mountain. And part of your job, aside from parsing abstract intellectual property issues for big corporations, is to help cultivate the next set of young lawyers being courted by the firm. A senior partner asks if you’ll mentor an incoming summer associate, and the answer is easy. Of course you will. You have yet to understand the altering force of a simple yes. You don’t know that when a memo arrives to confirm the assignment, some deep and unseen fault line in your life has begun to tremble, that some hold is already starting to slip. Next to your name is another name, that of some hotshot law student who’s busy climbing his own ladder. Like you, he’s black and from Harvard. Other than that, you know nothing—just the name, and it’s an odd one. (pp. 92–93)

Their acquaintance with one another begins, “Barack Obama was late on day one.” (p. 94) She’s a high-powered lawyer, but she doesn’t much like the isolation that young associates faced grinding out billable hours. She forged relationships with some people in the firm, and “I fortified myself with daily check-ins with my mom and dad. I’d hugged them that very morning, in fact before dashing out the door and driving through a heavy rainstorm to get to work. To get to work, I might add, on time.

“I looked at my watch.

“‘Any sign of this guy?’ I called to Lorraine [her assistant].

“Her sigh was audible. ‘Girl, no’ she called back. She was amused, I could tell. She knew how tardiness drove me nuts—how I saw it as nothing but hubris.” (p. 96)

She’s doubtful about the new guy arriving with a hot-shot reputation. “Word had spread that one of his professors at Harvard—the daughter of a managing partner—claimed he was the most gifted law student she’d ever encountered. … I was skeptical of all of it. In my experience, you put a suit on any half-intelligent black man and white people tended to go bonkers.” (p. 96) When he does show up, “He grinned sheepishly and apologized for his lateness as he shook my hand. He had a wide smile and was taller and thinner than I’d imagined he’d be—a man who was clearly not much of an eater, who also looked fully unaccustomed to wearing business clothes. If he knew he was arriving with a whiz-kid reputation, it didn’t show.” (p. 97)

Later that day, she takes him out to lunch, as part of making summer associates happy and willing to commit to working for the firm after graduation. “What struck me was how assured he seemed of his own direction in life. He was oddly free from doubt, though at first glance it was hard to understand why. Compared with my own lockstep march toward success, the direct arrow shot of my trajectory from Princeton to Harvard to my desk on the forty-seventh floor, Barack’s path was an improvisational zigzag through disparate worlds. … Barack was serious without being self-serious. He was breezy in his manner but powerful in his mind. It was a strange, stirring combination.” (pp. 97–98)

His background included not just Harvard and Columbia, not just Hawaii and Indonesia, but Chicago too. “Barack was the first person I’d met at [the law firm] who had spent time in the barbershops, barbecue joints, and Bible-thumping black parishes of the Far South Side. Before going to law school, he’d worked in Chicago for three years as a community organizer … As he described it, it had been two parts frustration to one part reward … He was in law school, he explained, because grassroots organizing had shown him that meaningful societal change required not just the work of the people on the ground but stronger policies and governmental action as well.” Michelle continues, “Despite my resistance to the hype that had preceded him, I found myself admiring Barack for both his self-assuredness and his earnest demeanor. He was refreshing, unconventional, and weirdly elegant. Not once, though, did I think about him as someone I’d want to date.” (p. 98)

As his mentor, she also introduces him to some of the social sides of being an up-and-coming lawyer in Chicago. The story of how he didn’t get invited to a second cocktail party is a hoot and includes the sentences, “But he was a grown man. I let him rescue himself.” (p. 101) … Michelle draws some conclusions, “Barack was cerebral, probably too cerebral for most people to put up with. … He wasn’t a happy-hour guy, and maybe I should have realized that sooner. My world was filled with hopeful, hardworking people who were obsessed with their own upward mobility. … Barack was more content to spend an evening alone, reading up on urban housing policy. As an organizer, he’d spent weeks and months listening to poor people describe their challenges. His insistence on hope and the potential for mobility, I was coming to see, came from an entirely different and not easily accessible place.” (p. 101)

Her life is about to take what she would describe as a giant swerve, and although I have quoted so much from what she writes about her early years, I have left out so much that is so good. Her father has multiple sclerosis, yet never misses a day of work even as his mobility becomes impaired. Her mother’s firm, no-nonsense, resolutely non-helicoptery approach to parenting. The rich variety of relations who provide so many lively contrasts. Her storytelling connects the indelible individuality of her life with the larger streams of American life, both as how they manifest in Chicago and how they shape the wider contexts of her experience.

It’s all immensely readable, enjoyable, enlightening. As I have written this commentary and selected bits to quote, I found myself drawn back in, happily re-reading page after page. It’s just as good the second time around, and probably will the third and fourth times too. What happens next with Michelle and Barack is both known and unknown, and I hope to write more about it soon.

1 pings

[…] impress Michelle. Let me also stipulate that A Promised Land is not as relatable as Becoming, not a finely honed work executed with the utmost craftsmanship, designed to show how an ordinary girl from the South Side […]