Two years and some-odd weeks ago, Donald Fucking Trump — aided by the Russian government along with its witting and unwitting stooges, boosted by an FBI director he soon fired, slavered over by a national press that apparently couldn’t help itself any more than it could help spending more time on his opponent’s e-mail practices than all other issues combined, and, finally, selected by fools the length and breadth of the land — assembled a fortuitously placed minority of votes, and secured enough of the Electoral College to make him the forty-fifth president of the United States.

I didn’t see it coming. (I was in good company there.) In the months leading up to the election, I joked that Trump might go the full Mondale — losing all 50 states. I underestimated how difficult it is for a political party to hold the White House for three consecutive terms. Since World War II, that has happened exactly once. I underestimated the willingness of the press to dwell on trivia on one side of the ballot, and make it seem equivalent to serious matters on the other side. I underestimated the accumulated effects of a quarter of a century of bile spewed at Hillary. Most of all, I underestimated misogyny.

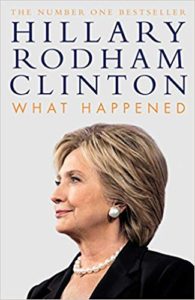

In What Happened, which I still think is missing two words from its title, Clinton reckons with the campaign, the election, and a short period afterward. On the inaugural that might have been hers, she relays the quote attributed to George W. Bush, “That was some weird shit.”

She lays out some of the structural constraints in the chapter “On Being a Woman in Politics”:

Meanwhile, when a woman lands a political punch — and not even a particularly hard one — it’s not read as the normal sparring that men do all the time in politics. It makes her a “nasty woman.” A lot of women have had that spat in their faces (and worse) for saying not that much at all. God forbid that two women have a disagreement in public. Then it’s a catfight.

In short, it’s not customary to have women lead or even to engage in the rough-and-tumble of politics. It’s not normal — not yet. So when it happens, it often doesn’t feel quite right. That may sound vague, but it’s potent. People cast their votes based on feelings like that all the time. (p. 121)

[Much younger me thought George H.W. Bush was kind of a weenie, and that made pulling the lever for his opponent, which I was inclined to do anyway, much easier. Clinton is exactly right that people vote for all kinds of reasons.]

I think this question of ‘rightness’ is connected to another powerful but undefinable force in politics: authenticity. I’ve been asked over and over again by reporters and skeptical voters, “Who are you really?” It’s kind of a funny question when you think about it. I’m Hillary. You’ve seen me in the papers and on your screens for more than twenty-five years. I’ll bet you know more about my private life than you do about some of your closest friends. You’ve read my emails, for heaven’s sake. What more do you need? What could I do to be ‘more real’? Dance on a table? Swear a blue streak? Break down sobbing? That’s not me. And if I had done any of those things, what would have happened? I’d have been ripped to pieces. (pp. 121–22)

She’s surely right about that.

Again, I wonder what it is about me that mystifies people, when there are so many men in politics who are far less known, scrutinized, interviewed, photographed, and tested. Yet they’re asked so much less frequently to open up, reveal themselves, prove that they’re real.

Some of this has to do with my composure. People say I’m guarded, and they have a point. I think before I speak. I don’t just blurt out whatever comes to mind. It’s a combination of my natural inclination, plus my training as a lawyer, plus decades in the public eye where every word I say is scrutinized. But why is this a bad thing? Don’t we want our Senators and Secretaries of State — and especially our Presidents — to speak thoughtfully, to respect the impact of our words? (p. 122)

It’s not just double standards: “There’s another thing that women confide in me about, and that’s stories of their reproductive health. No essay about women in politics could be complete without talking about this.” (p. 130) If it were up to the men in the race, it wouldn’t be brought up at all. “I was dismayed when Bernie Sanders dismissed Planned Parenthood as just another part of the ‘establishment’ when they endorsed me over him. Few organizations are as intimately connected to the day-to-day lives of Americans from all classes and backgrounds as Planned Parenthood, and few are under more persistent attack. I’m not sure what’s ‘establishment’ about that, and I don’t know why someone running to be the Democratic nominee for President would say so.” (pp. 130–31)

Her opponent from the Democratic primary earns more criticism: “Bernie Sanders, who loved to talk about how ‘true progressives’ never bow to political realities or powerful interests, had long bowed to the political reality of his rural state of Vermont and had supported the NRA’s key priorities, including voting against the Brady Bill five times in the 1990s.” (pp. 185–86) And later: “The delegate math hadn’t been in question since March, but Bernie had hung on to the bitter end, drawing blood wherever he could along the way. I somewhat understood why he did it; after all, I stayed in the race for as long as I could in 2008. But that race was much closer, and I endorsed Barack right after the last primary. On this day [June 7, 2016, the day of the final Democratic primaries] in New York, Bernie was still more than a month away from endorsing me.” (p. 244)

She insists on being reality-based, for instance on West Virginia voters, on energy and employment, and on what the working class looks like.

The first: “Some on the left, including Bernie Sanders, argue that working-class whites have turned away from Democrats because the party became beholden to Wall Street donors and lost touch with its populist roots. It’s hard to believe that voters who embrace Don Blankenship are looking for progressive economics. After all, by nearly every measure, the Democratic Party has moved to the left over the past fifteen years, not to the right. Mitt Romney was certainly not more populist than Barack Obama when he demolished him in West Virginia.” (p. 276)

The second: “The entire debate over coal unfolds in a kind of alternative reality. … [I]t’s been twenty-five years since the industry accounted for even 5 percent of total employment in [West Virginia]. … Across the country, Americans have more than twice as many jobs producing solar energy as they do mining coal. And think about this: since 2001, a half million jobs in department stores across the country have disappeared. That’s many times more than were lost in coal mining.” (p. 283) Of course there’s a gendered aspect to department store jobs and coal mining jobs.

The third: “More broadly, we remain locked into an outdated picture of the working class in America that distorts our policy priorities. … But fewer than 10 percent of Americans today work in factories and on farms, down from 36 percent in 1950. Most working-class Americans have service jobs. They’re nurses and medical technicians, childcare providers and computer coders. Many of them are people of color and women. In fact, roughly two-thirds of all minimum-wage jobs in America are held by women.” (pp. 283–84)

Her section about Russian meddling is looking more and more like it understates the case. If anything, she spends too little time on Trump’s systematic corruption. No president has had so many close advisers convicted of serious crimes. No president’s personal foundation, business organization, inaugural committee, and campaign have been revealed to be so corrupt on so many levels. No national security adviser has pled guilty to lying to the FBI, much less lying about failing to report foreign influence on him and his policies. There is a very real chance that Trump has been blackmailable, and for years.

“The election was decided by 77,744 votes out of a total of 136 million cast. If just 40,000 people across Wisconsin, Michigan, and Pennsylvania had changed their minds, I would have won.” (p. 394) What might have been.

The book itself reads quickly. Clinton tells the various stories conversationally and thoughtfully. Nearly halfway into the presidential term that followed the 2016 election, she was clearly right about so many things. It’s a shame that she had to write this book and not a presidential memoir, but it’s a clear-eyed diagnosis, and it shows how the campaign and its aftermath looked from the inside. Even if two words are missing from the title.

+++

Doreen’s review, which is better, is here.