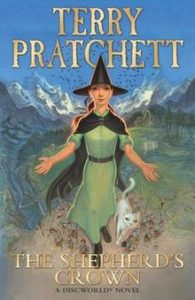

The Shepherd’s Crown is the end, and no way around it. The forty-first and last Discworld novel. After “The End” on page 328 there’s nothing more but what readers imagine might still happen on the Disc. Rob Wilkins, Pratchett’s chief assistant, writes in an afterword that The Shepherd’s Crown was “not quite as finished as [Pratchett] would have liked when he died.” It shows; quite a bit of the joists are still visible. On the other hand, that Pratchett was able to write a book at all, let alone one with as many splendid scenes as this one, while suffering from advancing Alzheimer’s surely counts as an act of magic worthy of a top graduate of the Unseen University.

One of the most affecting scenes is the extended sequence surrounding Granny Weatherwax’s death. On the Disc, witches and wizards know well in advance when Death is coming for them, and they each prepare in their own way. Granny Weatherwax tidies up, takes leave from all of the creatures near her cottage, and sets things up so that her chosen successor will find everything just as it should be.

Nanny Ogg’s words at the wake might also apply to Pratchett:

“No long faces for Granny Weatherwax, please,” Nanny proclaimed. “She’s had a good death at home, just as anyone might wish for. Witches know that people die, and if they manages to die after a long time, leavin’ the world better than they went an’ found it, well then, that’s surely a reason to be happy. All the rest of it is just tidyin’ up.” (p. 82)

Long faces or no, Granny’s death leaves two significant gaps that drive much of the story of The Shepherd’s Crown. First, there is the matter of her successor, not just in her newly tidied cottage up in Lancre, but as something like the voice of witchcraft. Second, among her many tasks Granny Weatherwax saw to it that the elves stayed in fairyland where they belonged, and not on the Disc, where they liked to come to play. The elves’ idea of play looked a lot like destruction to other people. Granny had seen them off more than once, most memorably in Lords and Ladies, but the elves kept probing, looking for a weakness in the Disc’s defenses so that they could cross over and frolic for a while. Or indeed for a long time.

“It’s you, Tiff. Esme’s left you her cottage. But more’n that. You must step into the shoes of Granny Weatherwax or else’n someone less qualified will try an’ do it!”

“But — I can’t! and witches don’t have leaders! You’ve just said that, Nanny!”

“Yes,” said Nanny. “And you must be the best damn leader that we don’t have. Don’t look at me sideways like that, Tiffany Aching. Just think about it. You didn’t try to earn it, but earn it you has, and if you don’t believe me, believe Granny Weatherwax. She tol’ me you that you was the only witch who could seriously take her place, she said that on the night after you run with that hare.”

“She never said anything to me,” said Tiffany, feeling suddenly very young.

“Well, she wouldn’t say nothing, o’ course she wouldn’t,” said Nanny. “That’s not Esme’s way, you know that. She would have given a grunt, and maybe said, ‘Well done, girl.’ She just liked people to know their own strengths — and your strengths are formidable.” (p. 75)

Not all of the other witches see it that way at first, but they soon come around. Granny’s cat, You, takes a particular liking to Tiffany, and Pratchett hints that there is a bit of Granny in You, too.

The middle of the book has Tiffany running herself ragged, trying to be witch of the Chalk while simultaneously looking after Granny’s steading in the Lancre mountains. It’s a familiar problem, deriving from Tiffany’s proud and helpful character. She wants to help the people who need it; she wants to do her duties as a witch; she wants to live up to the faith that Granny and the other witches put in her; and she is too proud to say that it’s all too much for her. It is, of course, and it’s about this time that the elves start to exploit the weaknesses that Granny’s absence have left open.

But Granny’s death is not the only way that the world has changed. The Disc is not what it was in Lords and Ladies. Not just the clacks and the newspapers and the banks and the post office. The iron horse has come to the Disc, and the elves cannot abide iron. Change is what The Shepherd’s Crown is ultimately about: what changes and what doesn’t, how to keep renewing traditions so that they stay vibrant, how things that can’t change don’t last.

The afterword suggests that Pratchett had numerous ideas for additional Discworld books “a second book about the redoubtable Maurice as a ship’s cat” or “the secret of the dark cave and carnivorous plants in The Dark Incontinent,” but it can equally be said that The Shepherd’s Crown is an ending. Magic is still everywhere on the Disc, but it is fading into the background as the changes pioneered in Ankh-Morpork reach into every nook and cranny. Earlier in the book, the Archchancellor of the Unseen University speaks of people who have so much power they never exercise it. At that same university, the first general-purpose computer becomes increasingly perspicacious. The series that began in an apparently timeless fantasy setting ends with railroads, telegraphs, and newspapers. There would have been more stories to tell about life on the Disc, but they would have owed more to Dickens than to Malory or Spenser. And so, in the new era, a young woman has the last words.